When Americans talk about guns, what’s arguably most interesting isn’t what we say about the devices themselves. It’s what we betray about whose voices — and lives — matter when it comes to our country’s virulent gun culture.

Recall the killing of Philando Castile, a 32-year-old Black man. In July 2016, two police officers pulled him over in a Saint Paul, Minnesota, suburb. When Castile, buckled into his seat, reached for his ID, he informed one of the officers, Jeronimo Yanez, that he had a gun — one that he was legally permitted to carry. Presumably familiar with the horrors that the police tend to visit on Black Americans, Castile just wanted to ward off any trouble. But Yanez lost control, hitting Castile with five of the seven shots he fired. Castile died later that night.

Instead of hurrying to condemn the shooting, as it had done when police officers killed White gun owners, the National Rifle Association initially sought refuge in saying nothing.

As Emory University African American studies professor Carol Anderson writes in her new book, “The Second: Race and Guns in a Fatally Unequal America,” “The NRA broke its silence only after inordinate pressure from African American members led the gun manufacturers’ lobby to issue a tepid statement that the Second Amendment was applicable ‘regardless of race, religion or sexual orientation.’ “

The NRA’s perfunctory response to Castile’s death shone a light on the way that race permeates the politics of gun control.

Decades ago, when Congress actually passed an assault weapons ban (one that, notably, was allowed to expire in 2004), the broad concern was around guns in the hands of people of color — Black Americans, specifically. Our modern Congress finds itself paralyzed now that we’re increasingly facing a different dimension of the issue: White people’s guns, and the consequences of their contested rights to have them.

Or as University of St. Thomas history professor Yohuru Williams says in the new CNN Films documentary, “The Price of Freedom,” “Throughout our history, the fear that African Americans could have access to firearms and use those firearms to the detriment of Whites is pervasive.”

Black self-defense

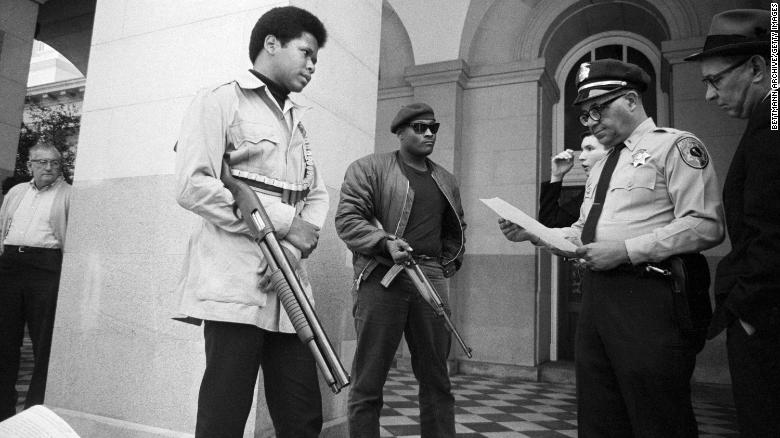

Understanding this history requires looking back at the social and political pieties that helped to spur the US’s contemporary gun rights movement. Consider how, in the 1960s, fear of the Black Panthers played a role in motivating conservative politicians — and even the NRA — to push for new gun control legislation. The Panthers, formed to challenge police brutality, advocated for Black self-defense via gun ownership and “copwatching.”

To no one’s surprise, the backlash against this vision of protection was swift. In 1967, in response to the Panthers’ activities, then-Gov. Ronald Reagan signed the Mulford Act, named after Republican Assemblyman Don Mulford and which repealed a California law that permitted people to carry loaded firearms in public.

Of the bill, Reagan said later that it’d “work no hardship on the honest citizen.” This citizen, we can assume, was White.

“The Mulford Act criminalized the open carry of firearms, and was designed specifically to disenfranchise and to disarm members of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense because they were demonstrating in public — carrying firearms openly to shed a spotlight on police violence against Black and brown people in California,” Harvard University historian Caroline Light says in “The Price of Freedom.”

Crucially, while unthinkable today, the NRA’s position on gun regulation until the late ’70s — when more and more (White) people began viewing guns as a means of protecting themselves and their status — was noticeably divorced from full-bore Second Amendment arguments, as UCLA School of Law professor Adam Winkler charts.

A different gun rights advocate

How distant all that seems now. These days, despite a resurgence in Black gun ownership, the face of the gun rights advocate has changed — rural White conservatives are now among the most vocal proponents.

Take, for instance, Missouri, where, in the past two decades, “an increasingly conservative and pro-gun legislature and citizenry had relaxed limitations governing practically every aspect of buying, owning and carrying firearms in the state,” writes Jonathan M. Metzl, a professor of sociology and psychiatry at Vanderbilt University, in his 2019 book, “Dying of Whiteness: How the Politics of Racial Resentment Is Killing America’s Heartland.”

“Corporate-gun-lobby-backed politicians, commentators and advertisements openly touted loosened gun laws as ways for white citizens to protect themselves against dark intruders,” Metzl explains. “Meanwhile, black men who attempted to demonstrate their own open-carry rights were attacked and jailed rather than lauded as freedom-loving patriots.”

Compare this with the rhetoric of the ’90s, when, on signing what became the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 (which contained the Federal Assault Weapons Ban), former President Bill Clinton said, “Gangs and drugs have taken over our streets and undermined our schools.”

It’s the difference between vanquishing the supposed specter of Black criminality — seen in gangs and the weapons associated with them — and protecting the property of White conservatives.

Or put another way, the hypocrisy around gun ownership in the US is a broadcast of something indisputably fundamental: the country’s struggle to bolster a racial hierarchy.

Two members of the Black Panther Party are met on the steps of the state capitol in Sacramento, California, May 2, 1967.

Two members of the Black Panther Party are met on the steps of the state capitol in Sacramento, California, May 2, 1967.