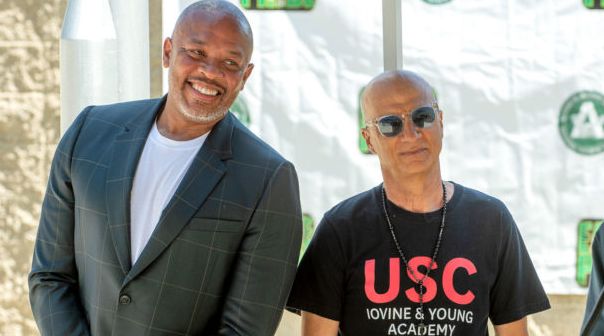

Rap icon Dr. Dre and music industry mogul Jimmy Iovine hated school — really hated school — which makes them an unlikely force behind a new public high school project in Los Angeles.

The two, both reportedly billionaires, said they would do and spend whatever is necessary to make the school, which will be in South L.A., successful and sought after — and a place that will motivate L.A. students to be critical thinkers, entrepreneurs and innovators. The move represents a rare investment by the entertainment elite in the nation’s second-largest school system, where more than 80% of students are Latino and Black and about the same number come from low-income families.

Dr. Dre, born Andre Young, said he wants to reach “the inner-city kid, the younger me.” He added: “Here’s a place that you can go where there’s something that you can learn that you’re really interested in.”

Iovine explained their vision for the school, which was approved last week by the L.A. Board of Education and is slated to open in fall 2022.

“This is for kids who want to go out and start their own company or go work at a place… like Marvel, or Apple or companies like that,” he said.

Working successfully in these areas means breaking down silos between different jobs and skills — and disrupting familiar patterns with creativity and purpose, Iovine said.

“This is nowhere near a music school,” he said.

In an interview at his Brentwood Country Estates home, Dr. Dre also spoke about his health — he had a scare in January. But he was focused first on describing the kind of L.A. youth who could benefit from the school.

“That guy that didn’t have an opportunity, that had to scratch and figure out things on his own,” he said. “That had the curiosity but didn’t have these type of opportunities, really smart kids — we want to touch and give them this open door and these opportunities to be able to show what they can do.”

Regional High School No. 1, as it’s known for now, will be located at Audubon Middle School in Leimert Park, a longtime Black cultural hub, but in a larger community where many Black and Latino students have struggled with low achievement.

Middle-class Black families in the area have largely abandoned local schools, sending children to independent charter schools or campuses to the west, including Westchester High and Venice High, said school board member George McKenna, who represents the area.

“What can we do about a community that seems to run away from, if I may use that term, their own schools and look elsewhere?” said McKenna, the only Black member on the Board of Education. “What we’re trying to do now is be persuasive — not just with with rhetoric, but with reality.”

The new school will be a “magnet,” meaning that students can apply from across the sprawling district. Transportation will be provided for those outside the local area. The school is among 10 magnets that educators approved last week.

Originally, magnets were created to spur voluntary integration, attracting white students to neighborhoods of color, and to keep their families invested in the public school system. These days, however, a primary goal is to attract any student — in L.A. Unified, enrollment is declining by about 2% a year.

Although some long-established magnets have waiting lists, it’s not been enough to reverse enrollment declines. Factors contributing to the enrollment drop — besides competition from charters — include gentrification, falling birth rates and reduced immigration.

L.A. schools Supt. Austin Beutner said the district has an obligation to find new, better and more engaging programs. The Dr. Dre-Iovine effort, he said, could create “the coolest high school in America.”

“We can better connect what a student learns in a high school today with a job opportunity in the future,” he said.

When the proposal came before the Board of Education, the trustees had concerns: There already are far more available classrooms than needed, and a high school this proposed size — about 250 students — would be financially unsustainable based on state funding levels.

What they didn’t know — because Beutner was holding details close for a splashy reveal Monday — is that Dr. Dre and Iovine are certain their school will be the grand exception. It also helps that USC will contribute expertise. Since 2013, USC has managed its own Iovine and Young Academy for Arts, Technology and the Business of Innovation, with a similar approach geared toward college and graduate students.

The concept is to engage students as future entrepreneurs and real-world problem-solvers, said Erica Muhl, founding dean of the USC academy, launched with a $70-million gift from the pair. At the academy, teams of students with different skills and roles tackle an issue or problem together in an “impact lab” — typically in collaboration with experts from private industry and nonprofits.

One project has been to improve the patient experience and better integrate the work of medical professionals at a new medical center. Another project helped lay the groundwork for the new high school, which is intended to mirror the model of the USC program.

Similarly, the high school version will incorporate high-tech equipment and projects with private industry. A task could have something to do with music or incorporate an element of music. But as Iovine said, this is no music school or Hip Hop High.

The school will join a relatively short list of education projects initiated by the wealthy from sports or entertainment. That list includes former Phoenix Suns star Kevin Johnson, who started charter schools in Sacramento. LeBron James catalyzed a new public school in Akron, Ohio.

Broadly speaking, the wealth of L.A. — its foundations and citizens — has barely been tapped on behalf of public schools, Beutner said, while noting that L.A. Unified has not always been easy to work with.

Iovine, 68, and Dr. Dre, 56, said they felt compelled to give back and determined to launch a high school — and both were drawn to South L.A.

The labyrinthine challenge of the L.A. Unified bureaucracy presented an opportunity, Iovine said.

“We want to do it in the public system,” he said. “We wanted to go to where it’s most needed — and it’s most difficult. And we will not be satisfied if this doesn’t scale. We want people inspired enough to scale it.”

And while they praised district staff, the project has been challenging, they said.

Dr. Dre said it was perplexing and frustrating to learn “how difficult it is to do something positive and to help.”

Both said they’re in it for the long haul, something that was a question mark after Dr. Dre had what was widely reported as a possible brain aneurysm in January.

“It’s a really weird thing,” he said. “I’ve never had high blood pressure. And I’ve always been a person that has always taken care of my health. But there’s something that happens for some reason with Black men and high blood pressure, and I never saw that coming. But I’m taking care of myself. And I think every Black man should just check that out and make sure things are OK with the blood pressure. And I’m going to move on and, hopefully, live a long and healthy life. I’m feeling fantastic.”

Dr. Dre grew up in Compton and attended Centennial High before transferring to Fremont High in South L.A. He rose to fame with the pioneering gangsta-rap group N.W.A, which drew its profane and poetically hard-driving lyrics from the Compton street scene. He went on to become an influential solo artist and producer, and co-founder with Iovine of Beats Electronics, which featured the successful headphones line Beats by Dr. Dre.

Iovine, from working-class roots, rose from music session engineer — working with artists such as John Lennon and Bruce Springsteen, to music mogul, co-founding Interscope Records in 1990 and becoming a longtime collaborator and business partner with Dr. Dre. Both are known for discovering and mentoring musical talent, which helped make them rich and revered.

Iovine and Dr. Dre sold Beats Electronics to Apple in 2014 for a reported $3 billion, and both went on to work as executives for Apple.

Iovine, who said he attended stifling, uninspiring Catholic schools in his Italian South Brooklyn neighborhood, said it helped to have the example of a hard-working father. He recalled a childhood friend who had no such role model and died of a heroin overdose, a tragedy that is one of his inspirations for the school. The friend “was more talented than me, more gifted than me, funnier than me,” Iovine said. But “he didn’t have anywhere to use those talents, to express that.”

As a child, Dr. Dre somehow knew enough not to model himself after his father and uncle — both drug dealers, he said. Instead, he idolized musicians, a focus that gave him a path out.

Neither can recall a single educator who made a difference in their lives while growing up — except perhaps for the college science teacher who pulled Iovine aside and said: “This isn’t for you.” Iovine followed that advice — dropping out after a year.

Dr. Dre lasted two weeks in a college program.

“No kid wants to go to school,” Dr. Dre said. “Because it’s boring. You keep flipping the same thing over and over and over again, year after year, with the same curriculum, the same teachers.”

Yet, they also know their new venture will depend on teachers, whose importance they recognize.

“This is something new and different that might excite the kids and make them want to go to school,” Dr. Dre said.

He added: “I had no idea this is where my life and career was gonna go, and everything that I’ve been doing throughout my career … was gonna lead to this, all those things a stepping stone to get here. Is this what it’s supposed to be? The, you know, the Big Bang? Hopefully it is.”