America’s two political parties — Republicans and Democrats — are two sides of the same coin. While both parties are pitched as total opposites, their histories are forever linked. Although politics feel as old as America: animals and colors that represent each party were comically chosen to implicate America’s virtues.

Choosing between Republican or Democrat is a decision that is ultimately influenced by personal history and ethics. The first party officially starts in 1828 when Martin Van Buren, the eighth U.S. President, Andrew Jackson, the seventh U.S. president launched the Democratic party. The Republican party was created in 1854, yet neither donkeys or elephants were political icons until the 1870s.

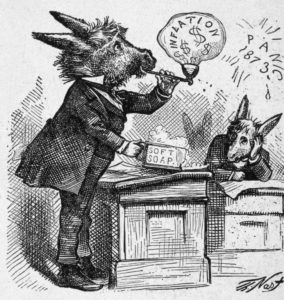

Through Jackson’s 1828 campaign, his opponents used “jackass” to insult him. He liked it and brandished donkey images on his campaign posters. Ultimately, Jackson was the last candidate to choose a long lasting icon for their respective party.

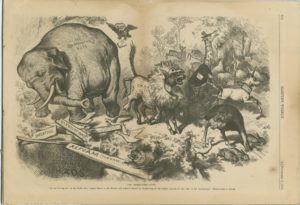

Republican’s elephant was taken from “seeing the elephant” which alluded to Civil War-era soldiers experiencing combat. The elephant was first used in a political cartoon. Although neither party would have an official animal until Thomas Nast’s cartoons in the 1870s.

Both party’s animals were popularized in Nast’s 1874 cartoon “Third Term Panic”. The cartoon showed a donkey in lion skin scaring off all other animals in frame except for an elephant labeled “the Republican vote”. “Third Term Panic” was the first cartoon to feature a donkey and elephant representing Democrats and Republicans.

Essentially, Nast chose the animals that are now popular party icons. But who were the first people to choose red and blue to represent the parties? This history begins in 1976 with the color-televised presidential race between Democratic Governor of Georgia, Jimmy Carter, and Republican incumbent Gerald Ford.

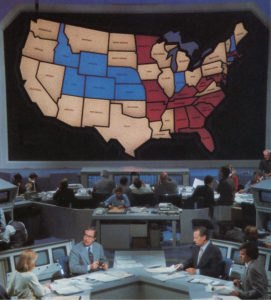

The televised election maps among TV-stations were not uniform. Maps showed different color combinations to indicate which states either candidate was winning. This confused some electorates, but not enough for substantial change then.

While strictly associated with Republicans today, red was thrown between parties, because of its iconographic association with Communism. As a constitutional federal republic, neither party wanted to be identified with red. This back-and-forth persisted until the 2000 election between President George W. Bush and Governor Al Gore.

Here, the electoral college vote took about 32-days to resolve and was finalized after the Supreme Court of the United States decided over Florida’s Supreme Court in favor of George Bush. TV stations did not take as long to decide on party colors and chose red for Republican and blue for Democrat sometime between November 10 and December 12, 2000.

Considering a full spectrum of potential color, choices red and blue seem arbitrary. Unlike the animals, nothing supports that any one person or group hand-picked red and blue. Regardless, color temperature relationship and color-theory significance offer intentional meanings between them.

Colors exist on a gamut, the electromagnetic color spectrum, that show every humanly-perceivable color. Color variations are visible through different light frequencies. There are potentially infinite colors, yet a simplified spectrum emphasizes seven colors.

All seven colors — red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet — makeup rainbows and a color wheel’s fundamental hues. Each hue has energy based on its frequency. As color energy increases, color temperature decreases. Hot and cold colors, like red and blue, clash because they have different energies.

Red and blue are not opposites though. Their energies clash like Republicans and Democrats, yet that does not mean red, blue, republican, nor democrats are inherently bad. In fact, colors psychologically influence consumer choices, therefore political leanings are shaped with persuasion in mind.

Political icons are marketing decisions that aim to guide electorates. Icons like party animals were entirely related to cartoons, propaganda, and marketing. Colors were chosen by TV-networks and both icons, chosen near randomly, make statements about the group they represent.

Red evokes power, dominance, and wealth. This makes sense when ideally, Republicans champion limited federal power and government regulation, therefore more power to the free-market system. Red is also exciting, yet aggressive which leads to potential danger evocation as it relates to blood and fire.

Extending to animal iconography, elephant wisdom and impeccable memory allude to Republican conservatism. “Seeing the elephant” was a wartime phrase, yet the elephant can represent power by its size. Together, elephant and red emphasize power and represent America’s lust for war and conflict.

Conversely, blue evokes stability, dependence, and strength. Democratic values include a strong federal government that is active in its constituent’s lives. Public programs that center those in need are characteristic of Democratic values, therefore blue rationalizes people’s dependence on the government.

Before the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century, donkeys were dependable beasts of burden for long travel. A donkey doubles down on Democratic symbolism by evoking dependence when divorced from politics. A blue donkey is a strong and stable symbol, similar to how Democrats aim to be viewed.

Despite how parties clash they are two sides of America’s political coin. Red or blue, Republican or Democrat, ideally both parties function for their constituents’ benevolence. Both parties agree on majority rule, so while they’re not balanced like yin-and-yang, they attempt to consider all populace, which is no assertion that either is better than the other.