Have traditional civil rights organizations and leaders lost their appeal among young people? Some would say yes, because they seem to appeal to silos, rather than exploring and accepting a range of modern ideologies. In many ways, Black people are approaching true freedom. Behind this realization, it appears that younger generations are distancing themselves from divisive organizations and leaders who function under the “respectable” politics of dominating, hegemonic institutions.

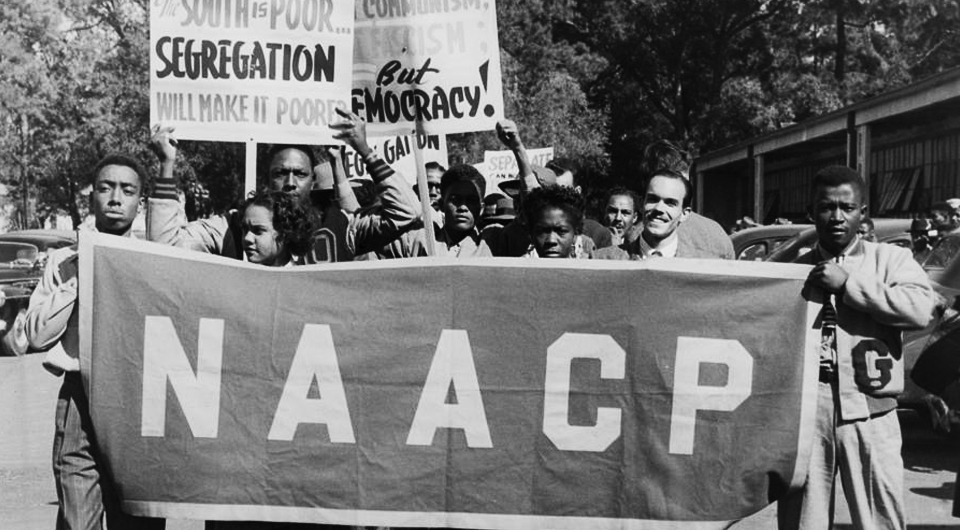

Since its founding in 1909, in response to the widespread lynching of African Americans and voter injustice permeating the South, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) has stood (and has the distinction of still being) the nation’s oldest and largest non-partisan civil rights organization. Similarly, the National Urban League (NUL) was born in New York in 1911 as a “community-based” organization conceived to provide transitional assistance to African Americans migrating from the South to Northern, urban centers, and also help them achieve economic and social justice.

In just the past few years, Black Lives Matter, or BLM, has evolved from a mere catchphrase to a loosely knit, less-than unified organization to become today’s respected national-international network addressing black issues, and the acronym that younger generations most readily cite, relate to and get involved with. There are other civil rights groups of course, like Al Sharpton’s National Action Network and Jesse Jackson’s Operation PUSH, but they don’t command the cache, influence or impact of the aforementioned membership organizations.

Love them or not, there are pros and cons, as the older groups are often viewed by younger generations as entry points into activism. Plus, any examination of the past lets young people know that throughout history and despite contributing massive effort toward Black liberation struggles, Black people were then, and continue to be spoken over, overlooked and denigrated. This pro—having a historically charged critical awareness—is also a con, because by informing via critical awareness, digital-age activists may resent certain movements, groups and people owing to their past affiliations and/or leanings.

The sacrifices, contributions and victories by the NAACP, NUL as well as others led to many cosmetic changes and some widespread empathy, yet conversely the concepts and ideologies they minimized are what organizers focus on now: Housing equity, trans/queer rights, dismantling prisons/police, etc. The progress they’ve achieved inform how people perceive African Americans—with respectability politics at its center. Over time, the contributions and struggles of past leaders were co-opted by the hegemony to control and numb contemporary movements. By that, I mean the legacies of past leaders are wielded against younger people today with sentiments like, “Well, what younger people are doing now in the streets isn’t what past leaders would have wanted. Therefore, it’s wrong and should be approached with more accepted, expected tactics.”

Results wise, however, old-guard civil rights organizations appear ineffective in the eyes of youth largely because they insist that Black people play the long game and achieve social equity by conforming to white supremacy and capitalist success. Civil rights groups have historically emphasized self-deprivation for slow progress, and neither are what younger generations want. Organizations like the NAACP and National Urban League strive for social equity among race groups through American politics. Their end goals are forcing America to accept Blackness, instead of guiding Black people to have agency in their own lifestyles.

Approaching equity through American politics often disregards the systemic racism and class conflicts that were intentionally woven into America’s fabric. Establishment civil rights organizations are outdated, because they romanticize being a “double agent” by striving for acceptance into the white world, and then making it implode.

Victories like the U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision, the 1964 Civil Rights Act and 1965 Voting Act passages have only hidden racial discrimination. Race-based segregation byway of redlining, structural racism and voter suppression are now quiet issues that still impact Black people. Races are integrated and attention has been given to curb prejudicial language, yet these are surface level fixes that never approach the root issue: White supremacy and Capitalism.

For too long, organizations have insisted that oppressed people change and agree on how they want to be viewed by outsiders. Instead of addressing the source of their issues, they reduce themselves to single expressions to make their identities more digestible. Zooming into single characteristics tries to mute a person’s range to uplift a group, but a group can’t unify unless individuals feel actualized in community.

Organizations speak to an aspect of a person, and therein lies the issue with charismatic movement leaders. They’re summed up to represent a movement, when they are multifaceted people after leaving their podiums.

Mass movements require charismatic leaders who can double as potential martyrs who may give their lives to immortalize the movement’s motivating idea. A movement’s motivating idea is its dogma and/or religion, which its loyalists are expected to follow. In this way, mass movement leaders move people in the manner that prophets would.

Believing that they’ve only realized minimal gains from past movements, it makes sense that younger generations want to blaze different paths. Contrary to some perspectives, young people attempt to be accountable for all parts of their being by exploring multiple aspects of their personalities, thus practicing self-acceptance. This leads to accepting and growing through imperfection. People can’t be summed into single identities, because they are products of multiple people, communities and environments. Acknowledging multiplicity is a major reason why younger generations rebuke leaders and singular focused organizations.

Younger generations won’t readily move with older organizations because the past styles of conformity don’t offer agency. There’s no reason for many of them to affiliate with divisive leadership and organizations because people now have the option and mandate to lead themselves—and feel free doing so every step of the way. However, if I’m honest here, at the end of the day the legacy civil rights groups are still direly needed and simply can’t go away any time soon. As American politics and the headlines alone have demonstrated, little has really changed for Black and brown communities.